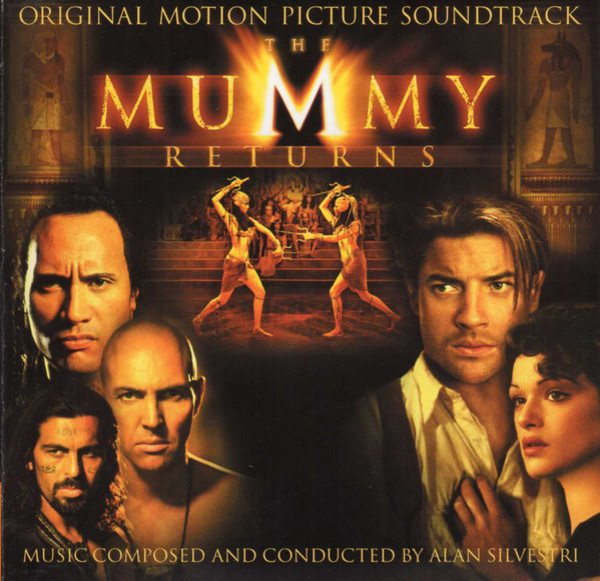

The Mummy Returns

Subscribe now!

Stay better informed and get access to collectors info!

Stay better informed and get access to collectors info!

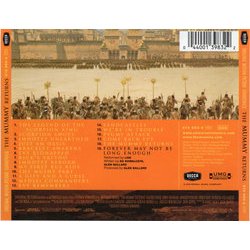

| # | Track | Artist/Composer | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | The Legend of the Scorpion King | 4:55 | ||

| 2. | Scorpion Shoes | 4:24 | ||

| 3. | Imhotep Unearthed | 4:22 | ||

| 4. | Just an Oasis | 1:25 | ||

| 5. | Bracelet Awakens | 1:28 | ||

| 6. | Evy Kidnapped | 5:55 | ||

| 7. | Rick's Tattoo | 1:59 | ||

| 8. | Imhotep Reborn | 2:42 | ||

| 9. | My First Bus Ride | 7:45 | ||

| 10. | The Mushy Part | 2:42 | ||

| 11. | A Gift and a Curse | 5:32 | ||

| 12. | Medjai Commanders | 2:03 | ||

| 13. | Evy Remembers | 4:03 | ||

| 14. | Sandcastles | 3:22 | ||

| 15. | We're in Trouble | 2:18 | ||

| 16. | Pygmy Attack | 3:31 | ||

| 17. | Come Back Evy | 3:29 | ||

| 18. | The Mummy Returns | 7:44 | ||

| 19. | Forever May Not Be Long Enough | Live | 3:47 | |

| 73:25 |

Submit your review

Show reviews in other languages

Stephen Sommers' films are not artistic masterpieces of deep emotional meaning. Some of them are downright dumb. But in terms of pure, adventurous fun, there are few directors who can match him. With his 1999 film The Mummy, Sommers produced what is probably the closest one can get to watching an Indiana Jones movie without actually watching an Indiana Jones movie (though Brendan Fraser will never be the next Harrison Ford). The highly popular score for that movie was composed by the legendary Jerry Goldsmith, and it was just as fun as its film, showing off some of Goldsmith's best action and adventure writing. Goldsmith quit the franchise with a bitter taste in his mouth, though, having made some well-publicized remarks about The Mummy's general stupidity as a film and how he, Goldsmith, didn't want such films to sour his resumé. Personally, I am baffled at this complaint against a dumb, but generally harmless film, especially coming from the composer of Rambo, but there you are.

Anyway, Sommers had to find himself a new composer for his decidedly inferior – though still enjoyable – follow-up film in 2001, The Mummy Returns. Enter Alan “ Back to the Future ” Silvestri, the hiring of whom was a laudably bold choice. Silvestri's heyday had been the 80s, with his writing in the 90s mostly (with exceptions such as Forrest Gump) avoiding the absolute forefront of the mainstream, straying instead into the realms of romantic comedies and schlocky, forgettable action films (for which he still provided above-average music, e.g. Judge Dredd, Volcano ). Sommers' choice, though, paid off and then some, with Silvestri providing a bombastic and swashbuckling action-adventure score that rivaled even John Debney's acclaimed and awesome work for Cutthroat Island. So impressed was Sommers, apparently, that he began a fruitful collaboration with Silvestri that led to the epic, supremely enjoyable Van Helsing in 2004, and the bland, but solid G.I. Joe: The Rise of Cobra in 2009.

This score begins anything but bland, though, with a five-minute highlight known as 'Legend of the Scorpion King'. At the outset, bass strings play a driving ostinato in their ominous lowest registers, over which horn fanfares build into an outburst of a choral, Oriental-sounding theme right out of the grand old-fashioned books of Miklos Rosza and the likes of El Cid. This moves on into a glorious, over-the-top action set-piece, with Silvestri all but overwhelming the listener with big martial rhythms, horn fanfares and that staple of true adventure music, cymbal rolls. The piece isn’t all action though – it has a lovely, quieter middle section featuring an English horn solo at 2:52. The simple fact that there’s an English horn in there at all shows just how fully orchestral this score is. In the days of film music that rarely evolves beyond conservative combinations of strings, brass, piano and percussion (real or synthetic), this is an extremely refreshing and impressive touch. The fully symphonic, 100-player presence extends all the way throughout the entire score, all 70 minutes of it.

Unfortunately, this brings me to one of the score’s weaker points – its album presentation. “What are you complaining about?” you might ask. “Seventy minutes of the best Alan Silvestri money can buy!” Well, I’ve always been cautious of longer albums. Once in a rare while, a movie does contain more than enough excellent and satisfying material to fill out not just one, but several discs – Howard Shore’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy or the aforementioned Cutthroat Island by John Debney being two prime examples. The curse of the long album on the other hand often strikes James Horner the hardest, leading to hour-plus albums such as A Beautiful Mind that deserve half their length – unfortunate considering Jerry Goldsmith’s albums often suffered from the opposite, and far worse, problem. Well, in this case, the long-album curse struck Silvestri. Not that the film doesn’t contain over seventy minutes of excellent music – it does! – but the album presents it badly, with a fair amount of suspenseful underscore and filler music making it onto the album, especially in its first half (“Imhotep Unearthed”, which does contain a notable bit of male ethnic wailing at 1:18, thankfully far from Gladiator-style; parts of “Evy Kidnapped”; “Imhotep Reborn”; “A Gift and a Curse” etc.). Adding an extremely dire insult to an ultimately acceptable injury, the highly enjoyable choral theme from the beginning of the end credits, laid over an ethnic drum rhythm, is omitted completely in favor of a horrendous rock song. This theme, representing the setting in a sweeping Maurice Jarre-esque, Lawrence of Arabia-styled way, does make several appearances in “A Gift and a Curse”, “Medjai Commanders”, “Sandcastles” and “We’re in Trouble”, but the choir and ethnic rhythm never combine the way they do in the credits suite. A final complaint is the fact that the penultimate track, “The Mummy Returns”, is simply an eight-minute concert arrangement cobbled together entirely from bits of the rest of the album. With so much strong material unreleased, it seems a shame to waste CD space with this sort of repetition.

But back to the music itself. Thematically, Silvestri’s work in The Mummy Returns is actually quite dense, composing six readily identifiable themes, as well as a few lesser motifs. There is next to no reference to the Jerry Goldsmith material, which may seem a shame considering how excellent the veteran composer’s three prominent adventure, villain and love themes were. But it's no matter, as the music Silvestri composes to fill these gaps is no less enjoyable. The theme you’ll be madly humming after the first listen is, of course, the infuriatingly catchy main adventure theme, representing Rick O’Connell, especially during his action sequences. It sounds like a marriage of Silvestri’s own Back to the Future theme with the fanfares of David Arnold’s Independence Day and, of course, John Debney’s Cutthroat Island, an absolutely supreme mixture. All three of these sources – the first via John Williams – can be traced back in history to the father of this swashbuckling type of music: Erich Wolfgang Korngold. And though it makes its album début at a slower and rather less enjoyable tempo in “Evy Kidnapped”, nowhere does this adventurous spirit better shine than in the absolute highlight of the score, the blazing eight-minute action extravaganza known as “My First Bus Ride”. Silvestri drives the Sinfonia of London – especially the brass and percussion players – to the very limits of their skill, to the point of there being a rather noticeable, almost jazzy-sounding horn flub at 1:09. There’s heroic fanfares aplenty over a driving 6/8 bass string rhythm, accompanied by Williams- and Debneyesque cymbal rolls and crashes, not to mention an audacious - almost to the point of annoying, but still enjoyable - set of fluttering piccolo arpeggios mixed so close to the forefront as to be nearly deafening. Rick’s theme appears frequently, interchanging towards the end with a secondary, Arnold-and-ID4-styled adventure theme that had already been hinted at, more softly, at 0:37 into “Just an Oasis”. Both swashbuckling themes crop up a few more times throughout the album, noticeably for the short but enjoyable “We’re in Trouble”.

The villain’s theme, such as it is, first appears towards the end of the cue “Imhotep Unearthed”, with reprises in “Rick’s Tattoo”, “Imhotep Reborn”, “My First Bus Ride” and “A Gift and a Curse”. It can barely be considered a theme, unfortunately – more of a recurring motif. It’s a two-note descending idea played on menacing low brass over plodding bass string or percussive rhythms. This is where the score most closely resembles Goldsmith's original, reminiscent of some of Goldsmith's villain underscore, minus the actual theme itself. Unfortunately, though this is no criticism of Goldsmith, this is probably Silvestri's greatest weakness in The Mummy Returns – the lack of a proper villain’s theme. Sure, it’s sufficient and effective underscore, and becomes quite entertaining when joined by a menacing, chanting male choir in “Rick’s Tattoo” or else as an action motif in “My First Bus Ride”. Considering Goldsmith’s wonderful theme for Imhotep in The Mummy, though – the theme appearing in grand fashion at the very outset of the film – this seems a bit of a letdown.

Absolutely not down-letting, on the other hand, are Silvestri’s love themes, of which there are two. Goldsmith composed a single, sweeping love theme for The Mummy that represented both the relationships; that between the heroes Rick and Evy, as well as that between the villains Imhotep and Anakh-su-Namun (that spelling’s probably off…). As the latter character plays a far more important role in this film than the first, a separate theme was necessary for the villains’ love, and it’s cleverly composed, sad enough to delinate the fact that these characters never do end up together, but also devious enough to remind us that these are the villains and we probably shouldn’t be feeling TOO sorry for them. It’s presented but once (not counting the reprise in the concert suite), on a solo violin at the beginning of “Evy Remembers”, followed by the entire string section. Like much of the score, it too has a definite and pleasing Golden Age feel to it, though not as obviously so as the spectacular love theme in Cutthroat Island.

Silvestri’s other love theme, that representing our good guys, is less sweeping, less openly romantic and maybe a little bit less enjoyable than Goldsmith’s, though by a minimal margin. The better word for it would be “tender”, a thing Silvestri can do exceedingly well (Forrest Gump, Contact, Cast Away ), and he certainly succeeds here. It’s a flute (rather than a piano in the aforementioned scores) that performs the ethnically-tinged theme most of the time, such as in “Just an Oasis”, “The Mushy Part” and “Medjai Commanders”. It’s not until the latter track that the theme finally sweeps into an all-out romantic crescendo.

To cover all this score’s themes, one should note that there’s also a tragically memorable one-off theme that play’s over Evy’s death, heard in “Come Back Evy” (as well as the suite), that explodes in a massive, sweeping (I’m using that word a lot, aren’t I) statement at 1:35. And then, of course, there's the, ahem, sweeping Lawrence of Arabia-esque theme representing the desert setting, which I already mentioned in the third paragraph.

Finally, a special mention must be made of Silvestri’s prominent use of choir in The Mummy Returns. His use of voices isn’t quite as outwardly explosive as it would later become in Van Helsing or Beowulf, but there is still some extremely exciting, very Egyptian-sounding chanting to be heard in the action music of “Evy Remembers”, alternating cleverly between male and female voices. It's very stereotypical music in a way - it sounds just like what a Western audience would expect Egyptian music to sound like, as inaccurate as this perception may be. But as this film isn't exactly struggling for historical accuracy, the slightly cheesy yet still awesome atmosphere created is perfect. The choir adds a real sense of magnificence elsewhere in the score as well, be it for a crescendo of fantasy as towards the end of the first track, or to add a dark air of menace to the villain’s motif, as in “Rick’s Tattoo”.

To wrap up this lengthy review, this score is a must-have for, at the very least, any fan of Alan Silvestri, though anybody who is even a casual fan of adventure scores should own a copy. Not just because it’s the score that returned Silvestri firmly to mainstream action-adventure scoring, an arena where he is among the best of the best. If you, like me, found Back to the Future to be rather thin in orchestration, then The Mummy Returns is a perfect example of that adventurous style beefed up to the absolute orchestral and choral max. The epic scale of this score is unparalleled by truly none in Silvestri’s career (even if I do find Van Helsing just a bit more entertaining at times). The only material that even comes close are perhaps the final three tracks of The Abyss, and even they pale in comparison to the majesty that Silvestri presents here. To list The Mummy Returns’ most basic ingredients (not that this score can be said to directly lift from any of these sources), this score is an amalgam of the composer’s Back to the Future (with a pinch of Judge Dredd melodramatics to taste), stirred together with the mightiest Miklos Rosza and Maurice Jarre scores and a generous helping of Korngoldian, Arnoldian and Debnian swashbuckle to create a glorious, over-the-top feast of a score that, to be fair, is worthy of a far superior film than The Mummy Returns. The only reason I hesitate to award this score a full house is its album presentation – the lack of the end credits, the unnecessary concert suite, the ten or so minutes of less interesting filler, the song. Other than that, you’d be doing yourself and those living across the street a massive favor by picking this one up. A true masterpiece of popcorn-entertainment scoring.

Anyway, Sommers had to find himself a new composer for his decidedly inferior – though still enjoyable – follow-up film in 2001, The Mummy Returns. Enter Alan “ Back to the Future ” Silvestri, the hiring of whom was a laudably bold choice. Silvestri's heyday had been the 80s, with his writing in the 90s mostly (with exceptions such as Forrest Gump) avoiding the absolute forefront of the mainstream, straying instead into the realms of romantic comedies and schlocky, forgettable action films (for which he still provided above-average music, e.g. Judge Dredd, Volcano ). Sommers' choice, though, paid off and then some, with Silvestri providing a bombastic and swashbuckling action-adventure score that rivaled even John Debney's acclaimed and awesome work for Cutthroat Island. So impressed was Sommers, apparently, that he began a fruitful collaboration with Silvestri that led to the epic, supremely enjoyable Van Helsing in 2004, and the bland, but solid G.I. Joe: The Rise of Cobra in 2009.

This score begins anything but bland, though, with a five-minute highlight known as 'Legend of the Scorpion King'. At the outset, bass strings play a driving ostinato in their ominous lowest registers, over which horn fanfares build into an outburst of a choral, Oriental-sounding theme right out of the grand old-fashioned books of Miklos Rosza and the likes of El Cid. This moves on into a glorious, over-the-top action set-piece, with Silvestri all but overwhelming the listener with big martial rhythms, horn fanfares and that staple of true adventure music, cymbal rolls. The piece isn’t all action though – it has a lovely, quieter middle section featuring an English horn solo at 2:52. The simple fact that there’s an English horn in there at all shows just how fully orchestral this score is. In the days of film music that rarely evolves beyond conservative combinations of strings, brass, piano and percussion (real or synthetic), this is an extremely refreshing and impressive touch. The fully symphonic, 100-player presence extends all the way throughout the entire score, all 70 minutes of it.

Unfortunately, this brings me to one of the score’s weaker points – its album presentation. “What are you complaining about?” you might ask. “Seventy minutes of the best Alan Silvestri money can buy!” Well, I’ve always been cautious of longer albums. Once in a rare while, a movie does contain more than enough excellent and satisfying material to fill out not just one, but several discs – Howard Shore’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy or the aforementioned Cutthroat Island by John Debney being two prime examples. The curse of the long album on the other hand often strikes James Horner the hardest, leading to hour-plus albums such as A Beautiful Mind that deserve half their length – unfortunate considering Jerry Goldsmith’s albums often suffered from the opposite, and far worse, problem. Well, in this case, the long-album curse struck Silvestri. Not that the film doesn’t contain over seventy minutes of excellent music – it does! – but the album presents it badly, with a fair amount of suspenseful underscore and filler music making it onto the album, especially in its first half (“Imhotep Unearthed”, which does contain a notable bit of male ethnic wailing at 1:18, thankfully far from Gladiator-style; parts of “Evy Kidnapped”; “Imhotep Reborn”; “A Gift and a Curse” etc.). Adding an extremely dire insult to an ultimately acceptable injury, the highly enjoyable choral theme from the beginning of the end credits, laid over an ethnic drum rhythm, is omitted completely in favor of a horrendous rock song. This theme, representing the setting in a sweeping Maurice Jarre-esque, Lawrence of Arabia-styled way, does make several appearances in “A Gift and a Curse”, “Medjai Commanders”, “Sandcastles” and “We’re in Trouble”, but the choir and ethnic rhythm never combine the way they do in the credits suite. A final complaint is the fact that the penultimate track, “The Mummy Returns”, is simply an eight-minute concert arrangement cobbled together entirely from bits of the rest of the album. With so much strong material unreleased, it seems a shame to waste CD space with this sort of repetition.

But back to the music itself. Thematically, Silvestri’s work in The Mummy Returns is actually quite dense, composing six readily identifiable themes, as well as a few lesser motifs. There is next to no reference to the Jerry Goldsmith material, which may seem a shame considering how excellent the veteran composer’s three prominent adventure, villain and love themes were. But it's no matter, as the music Silvestri composes to fill these gaps is no less enjoyable. The theme you’ll be madly humming after the first listen is, of course, the infuriatingly catchy main adventure theme, representing Rick O’Connell, especially during his action sequences. It sounds like a marriage of Silvestri’s own Back to the Future theme with the fanfares of David Arnold’s Independence Day and, of course, John Debney’s Cutthroat Island, an absolutely supreme mixture. All three of these sources – the first via John Williams – can be traced back in history to the father of this swashbuckling type of music: Erich Wolfgang Korngold. And though it makes its album début at a slower and rather less enjoyable tempo in “Evy Kidnapped”, nowhere does this adventurous spirit better shine than in the absolute highlight of the score, the blazing eight-minute action extravaganza known as “My First Bus Ride”. Silvestri drives the Sinfonia of London – especially the brass and percussion players – to the very limits of their skill, to the point of there being a rather noticeable, almost jazzy-sounding horn flub at 1:09. There’s heroic fanfares aplenty over a driving 6/8 bass string rhythm, accompanied by Williams- and Debneyesque cymbal rolls and crashes, not to mention an audacious - almost to the point of annoying, but still enjoyable - set of fluttering piccolo arpeggios mixed so close to the forefront as to be nearly deafening. Rick’s theme appears frequently, interchanging towards the end with a secondary, Arnold-and-ID4-styled adventure theme that had already been hinted at, more softly, at 0:37 into “Just an Oasis”. Both swashbuckling themes crop up a few more times throughout the album, noticeably for the short but enjoyable “We’re in Trouble”.

The villain’s theme, such as it is, first appears towards the end of the cue “Imhotep Unearthed”, with reprises in “Rick’s Tattoo”, “Imhotep Reborn”, “My First Bus Ride” and “A Gift and a Curse”. It can barely be considered a theme, unfortunately – more of a recurring motif. It’s a two-note descending idea played on menacing low brass over plodding bass string or percussive rhythms. This is where the score most closely resembles Goldsmith's original, reminiscent of some of Goldsmith's villain underscore, minus the actual theme itself. Unfortunately, though this is no criticism of Goldsmith, this is probably Silvestri's greatest weakness in The Mummy Returns – the lack of a proper villain’s theme. Sure, it’s sufficient and effective underscore, and becomes quite entertaining when joined by a menacing, chanting male choir in “Rick’s Tattoo” or else as an action motif in “My First Bus Ride”. Considering Goldsmith’s wonderful theme for Imhotep in The Mummy, though – the theme appearing in grand fashion at the very outset of the film – this seems a bit of a letdown.

Absolutely not down-letting, on the other hand, are Silvestri’s love themes, of which there are two. Goldsmith composed a single, sweeping love theme for The Mummy that represented both the relationships; that between the heroes Rick and Evy, as well as that between the villains Imhotep and Anakh-su-Namun (that spelling’s probably off…). As the latter character plays a far more important role in this film than the first, a separate theme was necessary for the villains’ love, and it’s cleverly composed, sad enough to delinate the fact that these characters never do end up together, but also devious enough to remind us that these are the villains and we probably shouldn’t be feeling TOO sorry for them. It’s presented but once (not counting the reprise in the concert suite), on a solo violin at the beginning of “Evy Remembers”, followed by the entire string section. Like much of the score, it too has a definite and pleasing Golden Age feel to it, though not as obviously so as the spectacular love theme in Cutthroat Island.

Silvestri’s other love theme, that representing our good guys, is less sweeping, less openly romantic and maybe a little bit less enjoyable than Goldsmith’s, though by a minimal margin. The better word for it would be “tender”, a thing Silvestri can do exceedingly well (Forrest Gump, Contact, Cast Away ), and he certainly succeeds here. It’s a flute (rather than a piano in the aforementioned scores) that performs the ethnically-tinged theme most of the time, such as in “Just an Oasis”, “The Mushy Part” and “Medjai Commanders”. It’s not until the latter track that the theme finally sweeps into an all-out romantic crescendo.

To cover all this score’s themes, one should note that there’s also a tragically memorable one-off theme that play’s over Evy’s death, heard in “Come Back Evy” (as well as the suite), that explodes in a massive, sweeping (I’m using that word a lot, aren’t I) statement at 1:35. And then, of course, there's the, ahem, sweeping Lawrence of Arabia-esque theme representing the desert setting, which I already mentioned in the third paragraph.

Finally, a special mention must be made of Silvestri’s prominent use of choir in The Mummy Returns. His use of voices isn’t quite as outwardly explosive as it would later become in Van Helsing or Beowulf, but there is still some extremely exciting, very Egyptian-sounding chanting to be heard in the action music of “Evy Remembers”, alternating cleverly between male and female voices. It's very stereotypical music in a way - it sounds just like what a Western audience would expect Egyptian music to sound like, as inaccurate as this perception may be. But as this film isn't exactly struggling for historical accuracy, the slightly cheesy yet still awesome atmosphere created is perfect. The choir adds a real sense of magnificence elsewhere in the score as well, be it for a crescendo of fantasy as towards the end of the first track, or to add a dark air of menace to the villain’s motif, as in “Rick’s Tattoo”.

To wrap up this lengthy review, this score is a must-have for, at the very least, any fan of Alan Silvestri, though anybody who is even a casual fan of adventure scores should own a copy. Not just because it’s the score that returned Silvestri firmly to mainstream action-adventure scoring, an arena where he is among the best of the best. If you, like me, found Back to the Future to be rather thin in orchestration, then The Mummy Returns is a perfect example of that adventurous style beefed up to the absolute orchestral and choral max. The epic scale of this score is unparalleled by truly none in Silvestri’s career (even if I do find Van Helsing just a bit more entertaining at times). The only material that even comes close are perhaps the final three tracks of The Abyss, and even they pale in comparison to the majesty that Silvestri presents here. To list The Mummy Returns’ most basic ingredients (not that this score can be said to directly lift from any of these sources), this score is an amalgam of the composer’s Back to the Future (with a pinch of Judge Dredd melodramatics to taste), stirred together with the mightiest Miklos Rosza and Maurice Jarre scores and a generous helping of Korngoldian, Arnoldian and Debnian swashbuckle to create a glorious, over-the-top feast of a score that, to be fair, is worthy of a far superior film than The Mummy Returns. The only reason I hesitate to award this score a full house is its album presentation – the lack of the end credits, the unnecessary concert suite, the ten or so minutes of less interesting filler, the song. Other than that, you’d be doing yourself and those living across the street a massive favor by picking this one up. A true masterpiece of popcorn-entertainment scoring.

I think it would be fair to say that no matter how hard he tries, director Stephen Sommers is not going to be the next Steven Spielberg. The Mummy was a pretty good sub-Raiders of the Lost Ark type effort and after the surprising success of the format, a sequel was put into the works and so, in the grand tradition of the Batman films, we have The Mummy Returns (so, presumably looking forward to The Mummy Forever and then maybe Mummy & Daddy?) which is of course bigger, louder and more spectacular than the original. The original was campy fun, but the humour this time seems more strained and pathetic with what credibility the original had now dispersed by a deus ex machina riddled plot and some silly sequences that certainly sound like fun in theory, but are simply daft on screen and not aided by some sub-par effects work.

Jerry Goldsmith's exciting, tuneful original was warmly greeted on release and become one of his most popular scores for some years. However, Goldsmith subsequently revealed his dislike for the film and refused to score the sequel. Something Goldsmith should have done previously, on Rambo for example. It was with some rejoicing that the services of Alan Silvestri were summoned for the sequel and what an effort it is. In fairness, I mean that more along the lines of it simply being massive in scale and effect, even if it isn't actually as brilliant as it might have been. The opening is certainly impressive and comes across more as a golden age epic with some Alfred Newman style high end strings and Miklos Rozsa chorus. The use of the choir is fairly sparing, which definitely lends it more impact at suitable moments. Silvestri's music may be over the top by most standards, but he at least deploys his tactics with some modicum of common sense.

The sequel contains more outright action sequences than the first film (which is probably its biggest downfall - they just get tedious after a while) and Silvestri's action scoring has improved in almost every film culminating in probably his best genre effort, Judge Dredd. Indeed The Mummy Returns contains a few Dredd like moments in the darker, crushingly percussive and brass laden sections. Silvestri has also penned a nifty pair of action motifs which both appear in full flight during Evy Kidnapped. One is a David Arnold type affair, but the other is pure Silvestri, containing his favourite augmented fourth (as in the Back to the Future fanfare) as well as a short, surprising key change when the phrase repeats. Silvestri doesn't actually do much with either motif by way of variation, but wisely limits the number of appearances to prevent the thrill button approach from wearing too thin.

The quieter moments are the least interesting parts simply because the thematic material here isn't always as strong. A Gift and a Curse has lots of orchestral skittering, fine in a slow burn horror effort, but rather insubstantial here. The romantic theme for Rick and Evy is nice, but when given a subdued treatment simply can't hold its own against the bracing action music, but it serves well in a more epic Lawrence of Arabia type way. A new choral motif appears in Medjai Commanders and several reviewers have pointed out sounds like John Debney's SeaQuest theme. True enough, but for those whose soundtrack collection goes back further than 1977, it is even more similar to Rozsa's King of Kings. It works well and certainly gives the score some more dignity. The other choral moments contain some interesting effects as well as providing something approaching Goldsmith's 'march of the undead' type cues from the original in tracks such as Rick's Tattoo.

The music from the finale of the film isn't included, probably due to time constraints, however, The Mummy Returns is a perfectly thrilling album finale and from what I recall, the real finale music from the film offers little new. Forever May Not be Long Enough is a kind of lame hard rock song that tries to be edgy, but isn't. It doesn't quite fit, but it makes a change from yet another cheesy ballad. Overall, an interesting mixture of old and new styles that work better than the should. It is only really during the quieter sections does Silvestri need to sharpen the writing. Ideally they need to be a little more expansive or stronger thematically. They are nice unto themselves, but are simply overwhelmed here and the romance is certainly somewhat flat compared to Goldsmith's. Although the score is far from sounding disjointed, the relentless pace and choppiness of the film doesn't allow for quite the number of set piece cues that Goldsmith was afforded. Arnold had Independence Day, John Debney CutThroat Island and now this is Silvestri's mega epic score and it's quite a ride. Not perfect, but thrilling entertainment all the same.

Jerry Goldsmith's exciting, tuneful original was warmly greeted on release and become one of his most popular scores for some years. However, Goldsmith subsequently revealed his dislike for the film and refused to score the sequel. Something Goldsmith should have done previously, on Rambo for example. It was with some rejoicing that the services of Alan Silvestri were summoned for the sequel and what an effort it is. In fairness, I mean that more along the lines of it simply being massive in scale and effect, even if it isn't actually as brilliant as it might have been. The opening is certainly impressive and comes across more as a golden age epic with some Alfred Newman style high end strings and Miklos Rozsa chorus. The use of the choir is fairly sparing, which definitely lends it more impact at suitable moments. Silvestri's music may be over the top by most standards, but he at least deploys his tactics with some modicum of common sense.

The sequel contains more outright action sequences than the first film (which is probably its biggest downfall - they just get tedious after a while) and Silvestri's action scoring has improved in almost every film culminating in probably his best genre effort, Judge Dredd. Indeed The Mummy Returns contains a few Dredd like moments in the darker, crushingly percussive and brass laden sections. Silvestri has also penned a nifty pair of action motifs which both appear in full flight during Evy Kidnapped. One is a David Arnold type affair, but the other is pure Silvestri, containing his favourite augmented fourth (as in the Back to the Future fanfare) as well as a short, surprising key change when the phrase repeats. Silvestri doesn't actually do much with either motif by way of variation, but wisely limits the number of appearances to prevent the thrill button approach from wearing too thin.

The quieter moments are the least interesting parts simply because the thematic material here isn't always as strong. A Gift and a Curse has lots of orchestral skittering, fine in a slow burn horror effort, but rather insubstantial here. The romantic theme for Rick and Evy is nice, but when given a subdued treatment simply can't hold its own against the bracing action music, but it serves well in a more epic Lawrence of Arabia type way. A new choral motif appears in Medjai Commanders and several reviewers have pointed out sounds like John Debney's SeaQuest theme. True enough, but for those whose soundtrack collection goes back further than 1977, it is even more similar to Rozsa's King of Kings. It works well and certainly gives the score some more dignity. The other choral moments contain some interesting effects as well as providing something approaching Goldsmith's 'march of the undead' type cues from the original in tracks such as Rick's Tattoo.

The music from the finale of the film isn't included, probably due to time constraints, however, The Mummy Returns is a perfectly thrilling album finale and from what I recall, the real finale music from the film offers little new. Forever May Not be Long Enough is a kind of lame hard rock song that tries to be edgy, but isn't. It doesn't quite fit, but it makes a change from yet another cheesy ballad. Overall, an interesting mixture of old and new styles that work better than the should. It is only really during the quieter sections does Silvestri need to sharpen the writing. Ideally they need to be a little more expansive or stronger thematically. They are nice unto themselves, but are simply overwhelmed here and the romance is certainly somewhat flat compared to Goldsmith's. Although the score is far from sounding disjointed, the relentless pace and choppiness of the film doesn't allow for quite the number of set piece cues that Goldsmith was afforded. Arnold had Independence Day, John Debney CutThroat Island and now this is Silvestri's mega epic score and it's quite a ride. Not perfect, but thrilling entertainment all the same.

I actually enjoyed The Mummy quite a bit. I think it's the closest one can get to watching an Indiana Jones film, without actually watching an Indiana Jones film. Also, Goldsmith's score was one of the more entertaining action and adventure scores in recent years. So, what about the successful sequel, The Mummy Returns (what kind of lousy, unoriginal title is that, by the way)? Well, I haven't seen the film, but Alan Silvestri, brought in to score the film, instead of Goldsmith, who wasn't interested in doing the job, has sure done a great job providing the music.

Performed by a big orchestra, with prominent brass, supported by both female and male choir, as well as a few exotic, Arabian sounding instruments, this is an incredibly fun, swashbuckling, bombastic and adventurous listening experience. The main theme is big, brassy and heroic, reminiscent of Silvestri's classic theme for Back to the Future, given excellent renditions througout the score, but most prominently in "Evy Kidnapped" and the almost eight minutes long "My First Bus Ride" - one of the scores' highlights. There are also several other themes, buth this is the theme you'll be humming as you leave the theatre.

The Egyptian/Arabic influences are there of course, both when it comes to thematic material and harmony, and choices of instruments. Goldsmith's score revolved more around these ideas than Silvestri's though. This approach is of course rather stereotypical, and anything but original. But, hey, it works, and it's quite fun, so why not...!? And the usage of the full choir - although not overused - lends the music a very grand mystical and sometimes quite dark nature, that works really well.

The only negative aspect is that the score offers loud, bombastic action from start to finish. And to be frank it gets a little tiresome at times. Mostly towards the end of the disc. There are some softer parts, but they generally don't last long, before the action takes over the entire stage again.

The 70 minutes long soundtrack ends with the song "Forever May Not Be Long Enough", performed by Live. It's actually quite awful. And totally out of place.

Performed by a big orchestra, with prominent brass, supported by both female and male choir, as well as a few exotic, Arabian sounding instruments, this is an incredibly fun, swashbuckling, bombastic and adventurous listening experience. The main theme is big, brassy and heroic, reminiscent of Silvestri's classic theme for Back to the Future, given excellent renditions througout the score, but most prominently in "Evy Kidnapped" and the almost eight minutes long "My First Bus Ride" - one of the scores' highlights. There are also several other themes, buth this is the theme you'll be humming as you leave the theatre.

The Egyptian/Arabic influences are there of course, both when it comes to thematic material and harmony, and choices of instruments. Goldsmith's score revolved more around these ideas than Silvestri's though. This approach is of course rather stereotypical, and anything but original. But, hey, it works, and it's quite fun, so why not...!? And the usage of the full choir - although not overused - lends the music a very grand mystical and sometimes quite dark nature, that works really well.

The only negative aspect is that the score offers loud, bombastic action from start to finish. And to be frank it gets a little tiresome at times. Mostly towards the end of the disc. There are some softer parts, but they generally don't last long, before the action takes over the entire stage again.

The 70 minutes long soundtrack ends with the song "Forever May Not Be Long Enough", performed by Live. It's actually quite awful. And totally out of place.

This soundtrack trailer contains music of:

Redrum, Immediate Music (Trailer)

Cutthroat Island (1995), John Debney (Movie)

Romeo + Juliet (1997), Craig Armstrong (Movie)

Bram Stoker's Dracula (1992), Wojciech Kilar (Movie)

Naked Prey, Immediate Music (Trailer)

Trailer:

Trailer:

Redrum, Immediate Music (Trailer)

Cutthroat Island (1995), John Debney (Movie)

Romeo + Juliet (1997), Craig Armstrong (Movie)

Bram Stoker's Dracula (1992), Wojciech Kilar (Movie)

Naked Prey, Immediate Music (Trailer)

Trailer:

Trailer:

Soundtracks from the collection: The Mummy