The Lion In Winter / Mary, Queen of Scots

Silva Screen - FILMCD 353

Subscribe now!

Stay better informed and get access to collectors info!

Stay better informed and get access to collectors info!

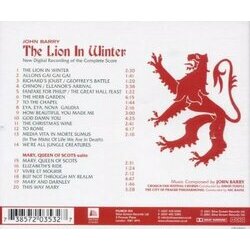

| # | Track | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Lion In Winter | |||

| 1. | The Lion In Winter | 2:28 | |

| 2. | Allons Gai Gai Gai | 1:40 | |

| 3. | Richard's Joust/Geoffrey's Battle | 1:19 | |

| 4. | Chinon/Eleanor's Arrival | 3:38 | |

| 5. | Fanfare For Philip/The Great Hall Feast | 1:22 | |

| 6. | The Herb Garden | 4:14 | |

| 7. | To The Chapel (Of Luv) | 1:45 | |

| 8. | Eya, Eya, Nova Gaudia | 2:15 | |

| 9. | How Beautiful You Made Me | 3:00 | |

| 10. | God Damn You | 4:28 | |

| 11. | The Christmas Wine | 2:40 | |

| 12. | To Rome | 4:28 | |

| 13. | media vita in morte sumus (In The Midst Of Live We Are In Death) | 2:05 | |

| 14. | We're All Jungle Creatures | 2:55 | |

| Mary, Queen Of Scots | |||

| 15. | Mary, Queen Of Scots | 2:31 | |

| 16. | Elizabeth's Ride | 1:23 | |

| 17. | Vivre Et Mourir | 2:11 | |

| 18. | But Not Through My Realm | 4:47 | |

| 19. | Mary And Darnley | 1:46 | |

| 20. | This Way Mary | 3:28 | |

| 54:22 |

Submit your review

Show reviews in other languages

After a series of very successful James Bond scores in the sixties, John Barry had ensured his place in the hall of fame of film music composers, as well as with the music public at large. The Bond scores immediately struck the chord with a large public, with their contemporary style. And then, in 1968, Barry scored the medieval drama The Lion in Winter, and the large public that had loved his Bond music and his more contemporary scores of the sixties was quite surprised by this dark, brooding, majestic score. However, that did not stop it from becoming a very loved score, and it caught the attention of the Academy that year, and Barry got his second score Oscar. Barry himself says in the liner notes that he believes he got the Oscar because The Lion in Winter was so different from his previous works, such a departure from the Bond scores. But he adds that really the Bond movies were the departure from his way of composing, not The Lion in Winter.

It is necessary to be on the clear from the beginning that The Lion in Winter is not an easy score. This is not the highly romantic Barry of later scores like Out of Africa or Dances with Wolves, and not the swingin’ Barry of the Bond scores. This is Barry at his most serious, The Lion in Winter being one of his darkest scores, heavy on low brass and strings, relying much more on textures than themes. And then the chorus of course – singing both lyrics in Latin, English and French as well as wordless chants – it is used to great effect, and sings both a capella and together with the orchestra. Basically, the chorus is what drives this score, even if the orchestral writing, especially the “dark” use of brass and strings, is quite extraordinary as well.

The main title really sets the tone for the rest of the score, introducing the score’s main theme, a quite harsh theme opening the cue on trumpet and high strings. The theme is developed further in the main title in the brass section, over a steady piano and timpani bass pulse, before the chorus powerfully enters the scene. Definitely one of the best tracks on the album with its exquisite dark power.

This main theme returns in a number of variations, mostly fragmentarily, in a couple of places. Otherwise, there is not much of melodic work in The Lion in Winter; at least, not of the hummable kind. Barry instead works a lot with different motivic cells, which he alters throughout the score in numerous ways. It can be heard when listening closely that there is a thematic unity in much of the music in this score, but it is nothing that will strike you as big themes, aside from the main theme, which is quite memorable. There is a very strong stylistic unity in the score though, which helps make it the very coherent work it in fact is.

While the choral work certainly is the main attraction of the score, the orchestral writing is worthy of a mention as well. Brass and strings are highly favoured throughout, while woodwinds mostly are absent. “God Damn You” is a great example of Barry’s string writing, which is quite elaborate, and deserves a close listen. The brass is used much to accentuate rhythms as well as bass lines, but there are also some thematic interplay inside the brass section, most notably in “To Rome”, where the brass really gets a workout, with the chorus’ soft chanting as background. The brass creates wonderful textures in these cues, and adds much to the drama of the music.

Because essentially, The Lion in Winter is dramatic underscore. Aside from the first two and the last track, the score is a dark, in turns both sombre and quite harsh, exquisitely dramatic exercise in underscore. And what really makes this shine is the chorus.

The best part of the choral work is definitely the wordless chanting utilised in most of the tracks (actually the chorus is present in all of the album’s tracks, so this can really be called a choral score). A highlight of this is “The Herb Garden”, opened by church bells, followed by a wonderful hushed polyphonic plainchant, almost otherworldly in character. All over, this chanting gives the score a rather religious feel, which also was what Barry wanted, according to the liner notes. There are also three “period” songs on the album, which all are decent songs, but nothing spectacular. They have a little too “cheery” feel to really merge with the score, and personally, they just don’t do anything for me. Moreover, the chorus is used to sing Latin text with the orchestra – this is very well used in the second track, “Chinon/Elanor’s Arrival”, a very beautiful track and quite different from the rest of the score. Here there are some thematic oboe and trumpet solos and a wonderful interplay between female and male chorus. Finally, the last tracks needs a mention too – a real highlight. This final cue is much lighter than the main body of the score, introducing a wonderful string melody, before knightly horns enter, heralding the entrance of the chorus which concludes the score triumphantly.

But, in the end, what lowers the rating of The Lion in Winter is after all the overall dark and harsh character of the score which makes it bit hard to digest, and to a lesser extent its lack of strong thematic work. If you are a real fan of dark choral underscore it can admittedly not get much better than this; but it nevertheless still lacks that ability to instantly enchant you, which would make it a real masterpiece. The Lion in Winter may, at first listen, even turn you away from it – it can seem both boring and rather uninteresting, being rather much similar from start to finish. It is however a very good score, and at the low price this original recording is sold at, I see no real reason not picking it up. But be warned: this is not an easily accessible score – it will take many listens before it sinks in and really grows on you. But, if you give it its time, I am perfectly sure that you will find the greatness of this dark score. It has a lot of personality, essentially being a very unique piece of work.

It is necessary to be on the clear from the beginning that The Lion in Winter is not an easy score. This is not the highly romantic Barry of later scores like Out of Africa or Dances with Wolves, and not the swingin’ Barry of the Bond scores. This is Barry at his most serious, The Lion in Winter being one of his darkest scores, heavy on low brass and strings, relying much more on textures than themes. And then the chorus of course – singing both lyrics in Latin, English and French as well as wordless chants – it is used to great effect, and sings both a capella and together with the orchestra. Basically, the chorus is what drives this score, even if the orchestral writing, especially the “dark” use of brass and strings, is quite extraordinary as well.

The main title really sets the tone for the rest of the score, introducing the score’s main theme, a quite harsh theme opening the cue on trumpet and high strings. The theme is developed further in the main title in the brass section, over a steady piano and timpani bass pulse, before the chorus powerfully enters the scene. Definitely one of the best tracks on the album with its exquisite dark power.

This main theme returns in a number of variations, mostly fragmentarily, in a couple of places. Otherwise, there is not much of melodic work in The Lion in Winter; at least, not of the hummable kind. Barry instead works a lot with different motivic cells, which he alters throughout the score in numerous ways. It can be heard when listening closely that there is a thematic unity in much of the music in this score, but it is nothing that will strike you as big themes, aside from the main theme, which is quite memorable. There is a very strong stylistic unity in the score though, which helps make it the very coherent work it in fact is.

While the choral work certainly is the main attraction of the score, the orchestral writing is worthy of a mention as well. Brass and strings are highly favoured throughout, while woodwinds mostly are absent. “God Damn You” is a great example of Barry’s string writing, which is quite elaborate, and deserves a close listen. The brass is used much to accentuate rhythms as well as bass lines, but there are also some thematic interplay inside the brass section, most notably in “To Rome”, where the brass really gets a workout, with the chorus’ soft chanting as background. The brass creates wonderful textures in these cues, and adds much to the drama of the music.

Because essentially, The Lion in Winter is dramatic underscore. Aside from the first two and the last track, the score is a dark, in turns both sombre and quite harsh, exquisitely dramatic exercise in underscore. And what really makes this shine is the chorus.

The best part of the choral work is definitely the wordless chanting utilised in most of the tracks (actually the chorus is present in all of the album’s tracks, so this can really be called a choral score). A highlight of this is “The Herb Garden”, opened by church bells, followed by a wonderful hushed polyphonic plainchant, almost otherworldly in character. All over, this chanting gives the score a rather religious feel, which also was what Barry wanted, according to the liner notes. There are also three “period” songs on the album, which all are decent songs, but nothing spectacular. They have a little too “cheery” feel to really merge with the score, and personally, they just don’t do anything for me. Moreover, the chorus is used to sing Latin text with the orchestra – this is very well used in the second track, “Chinon/Elanor’s Arrival”, a very beautiful track and quite different from the rest of the score. Here there are some thematic oboe and trumpet solos and a wonderful interplay between female and male chorus. Finally, the last tracks needs a mention too – a real highlight. This final cue is much lighter than the main body of the score, introducing a wonderful string melody, before knightly horns enter, heralding the entrance of the chorus which concludes the score triumphantly.

But, in the end, what lowers the rating of The Lion in Winter is after all the overall dark and harsh character of the score which makes it bit hard to digest, and to a lesser extent its lack of strong thematic work. If you are a real fan of dark choral underscore it can admittedly not get much better than this; but it nevertheless still lacks that ability to instantly enchant you, which would make it a real masterpiece. The Lion in Winter may, at first listen, even turn you away from it – it can seem both boring and rather uninteresting, being rather much similar from start to finish. It is however a very good score, and at the low price this original recording is sold at, I see no real reason not picking it up. But be warned: this is not an easily accessible score – it will take many listens before it sinks in and really grows on you. But, if you give it its time, I am perfectly sure that you will find the greatness of this dark score. It has a lot of personality, essentially being a very unique piece of work.

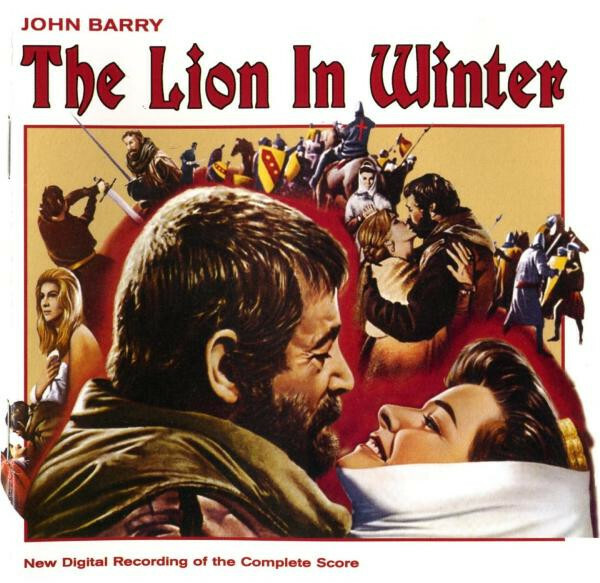

John Barry’s Oscar-winning score to the 1968 film The Lion in Winter has long been acknowledged as one of his most accomplished works with its complex, dark structure. An album of the near complete score has been in the market more or less from the film’s premiere, and still is. This did not stop Silva Screen Records though, who in 2001 produced a re-recording of the complete score, together with a suite from Barry’s score for the 1971 film Mary Queen of Scots, all performed by The City of Prague Philharmonic and the Crouch End Festival Chorus, conducted by Nic Raine. As for the length of the score, this recording adds only almost three minutes, and even if these two tracks are rather interesting, they do not alone merit buying this recording if you already own the original Sony album. But thanks to the inclusion of the Mary Queen of Scots suite and the improved sound quality compared to the original, this album can very well be worth the buy if you already own the Sony album – and a must-buy if you do not.

For the purely musical aspects of The Lion in Winter, I refer to my earlier review of the original score album. It is after all the same music on both albums, even if the experience is different due to a number of reasons, one of them being the inclusion of the two new tracks, making this release complete. But first and foremost, what separates this recording from the original is thirty years of recording engineering development. While the original recording sounded a little muffled at times, especially during the more delicate choral pieces, this recording is crisp and clear all the way through. This crisper sound is very evident in the final thundering part of “Media vita in morte sumus”, which on the original recording is muffled and distorted to the point where it is impossible to hear what really happens. On the Silva album it is crisp and even though it is a noisy piece, it is now clear what the orchestra and chorus really does in the piece.

Another field of improvement is the a capella choral pieces. On the Sony album I found them nasal and rather flat. I guess that is much due to the fact that they were background songs, and recorded without much dynamics, but they are anyway much better on this recording, where a more musical approach has been possible. Barry’s choral arrangements here come clear as brilliant as they really are, well performed by the Crouch End Festival Chorus.

Thanks to the improved sound quality, the listening experience improves with it, giving the listener a new perspective on the score. All the excellent orchestral and choral writing I mentioned in the original review gains even more depth out of this. The two new tracks are also great to hear, especially “Fanfare for Philip/The Great Hall Feast” – a quite jubilant piece, rather different from most of the score, opened with a long horn fanfare, followed by a cheery brass piece and rounded off by a wordless angelic female chorus. Other highlights include “The Herb Garden”, arguably the best cue of the score, with its wonderful wordless chanting, “How Beautiful you Made Me”, now even more powerful in its melancholy, and “Chinon/Elanor’s Arrival”, with its exquisite choral writing and thematic lyricism, another contender for the score’s best track.

But as everything, this recording is after all not perfect. There are some interpretative errors here and there, for example the slightly too high tempo of the main title, and at times it feels more mechanical, lacking the menacing aura that still makes the original recording very special. Ultimately though this is outweighed by the crisp sound and the fact that The Lion in Winter now finally can be enjoyed to its full extent, Barry’s complex writing standing completely clear.

On to Mary Queen of Scots then. The six track suite featured on this album clocks in at 16 minutes – not much but enough to get a picture of this nice score. It is based on a beautiful main theme introduced after a short fanfare opening right at the beginning of “Mary, Queen of Scots”, played on soft harpsichord, followed by strings, with a flute in counterpoint. A wonderful rendition of the theme on solo violin is also featured at the beginning of “This Way Mary”.

Aside from the beautiful lyrical thematic cues, the suite also contains some of the upbeat, sweeping brass and strings music Barry does so well, most notably in “But Not Through My Realm”. A more dramatic side of the score is also presented in “Mary and Darnley”, featuring a heartfelt, melancholic theme on strings. In fact, even if the suite is only 16 minutes in length, it displays a large array of different kinds of music, ranging from the beautiful to the sweeping to the sad and dramatic, and shows that Mary Queen of Scots is a great little score. Quite intimate all the way through, but quintessential Barry and a worthy addition to any Barry collection, even in this short form.

When I reviewed the original The Lion in Winter album, I gave it four stars. And for that album, I still stick to that rating. But, as it shows, in this complete and better-sounding recording, coupled with the wonderful Mary Queen of Scots suite, it adds up to a five star album. One of John Barry’s masterpieces and one of the greatest choral scores ever can, thanks to this recording, be enjoyed in crisp sound and in its complete form.

For the purely musical aspects of The Lion in Winter, I refer to my earlier review of the original score album. It is after all the same music on both albums, even if the experience is different due to a number of reasons, one of them being the inclusion of the two new tracks, making this release complete. But first and foremost, what separates this recording from the original is thirty years of recording engineering development. While the original recording sounded a little muffled at times, especially during the more delicate choral pieces, this recording is crisp and clear all the way through. This crisper sound is very evident in the final thundering part of “Media vita in morte sumus”, which on the original recording is muffled and distorted to the point where it is impossible to hear what really happens. On the Silva album it is crisp and even though it is a noisy piece, it is now clear what the orchestra and chorus really does in the piece.

Another field of improvement is the a capella choral pieces. On the Sony album I found them nasal and rather flat. I guess that is much due to the fact that they were background songs, and recorded without much dynamics, but they are anyway much better on this recording, where a more musical approach has been possible. Barry’s choral arrangements here come clear as brilliant as they really are, well performed by the Crouch End Festival Chorus.

Thanks to the improved sound quality, the listening experience improves with it, giving the listener a new perspective on the score. All the excellent orchestral and choral writing I mentioned in the original review gains even more depth out of this. The two new tracks are also great to hear, especially “Fanfare for Philip/The Great Hall Feast” – a quite jubilant piece, rather different from most of the score, opened with a long horn fanfare, followed by a cheery brass piece and rounded off by a wordless angelic female chorus. Other highlights include “The Herb Garden”, arguably the best cue of the score, with its wonderful wordless chanting, “How Beautiful you Made Me”, now even more powerful in its melancholy, and “Chinon/Elanor’s Arrival”, with its exquisite choral writing and thematic lyricism, another contender for the score’s best track.

But as everything, this recording is after all not perfect. There are some interpretative errors here and there, for example the slightly too high tempo of the main title, and at times it feels more mechanical, lacking the menacing aura that still makes the original recording very special. Ultimately though this is outweighed by the crisp sound and the fact that The Lion in Winter now finally can be enjoyed to its full extent, Barry’s complex writing standing completely clear.

On to Mary Queen of Scots then. The six track suite featured on this album clocks in at 16 minutes – not much but enough to get a picture of this nice score. It is based on a beautiful main theme introduced after a short fanfare opening right at the beginning of “Mary, Queen of Scots”, played on soft harpsichord, followed by strings, with a flute in counterpoint. A wonderful rendition of the theme on solo violin is also featured at the beginning of “This Way Mary”.

Aside from the beautiful lyrical thematic cues, the suite also contains some of the upbeat, sweeping brass and strings music Barry does so well, most notably in “But Not Through My Realm”. A more dramatic side of the score is also presented in “Mary and Darnley”, featuring a heartfelt, melancholic theme on strings. In fact, even if the suite is only 16 minutes in length, it displays a large array of different kinds of music, ranging from the beautiful to the sweeping to the sad and dramatic, and shows that Mary Queen of Scots is a great little score. Quite intimate all the way through, but quintessential Barry and a worthy addition to any Barry collection, even in this short form.

When I reviewed the original The Lion in Winter album, I gave it four stars. And for that album, I still stick to that rating. But, as it shows, in this complete and better-sounding recording, coupled with the wonderful Mary Queen of Scots suite, it adds up to a five star album. One of John Barry’s masterpieces and one of the greatest choral scores ever can, thanks to this recording, be enjoyed in crisp sound and in its complete form.

To go from Bond to the Middle Ages was undoubtedly a large leap for John Barry, even though he was a well respected film composer and Oscar winner (for Born Free). However, The Lion in Winter, while still retaining that quintessential Barry sound adds (unusually for Barry) a choir. From the well known, strident main title to the gentle and often very beautiful acappella performances it is a crucial component, chanting various Latin texts.

The acappella sections are generally in a mock middle age, plain song style, but those with the orchestra contain Barry's more 20th Century rhythms. In fact, the opening title track contains plenty of off the beat rhythms that are a wonderful mixture of the ancient sound, with Barry's own style and the dramatic needs of the film. It shouldn't work, but yet it does, splendidly. This version contains several cues that weren't contained on the original album, notably the early Joust and Battle cue and the splendid Fanfare for Philip and The Great Hall Feast.

Perhaps of more interest to Barry fans is a suite from Mary, Queen of Scots. It's unfortunate that more from this score couldn't have been included as it's up there on the list of Barry scores that really ought to see the light of day on CD. The main theme is familiar from compilations, quite lovely in its simplicity. The highlights are perhaps the less familiar parts, the jaunty But Not Through My Realm being particularly wonderful; a bouncing woodwind figure over which is placed a longer line string melody.

The performance by the Prague Orchestra and Crouch End Festival Orchestra are typically excellent. They always are with their Barry performances, although I'd suggest that The Lion in Winter is more taxing than typical Barry. For The Lion in Winter, the better sonics are a definite bonus over the slightly harsh original album and of course the extra cues are of interest. This is likely the best we can hope for with regard to Mary, Queen of Scots, but it's a tempting sample from another great score. One great Barry score and a taste of another for the price of one make it well worth picking up, even if you already have the original Lion in Winter album.

The acappella sections are generally in a mock middle age, plain song style, but those with the orchestra contain Barry's more 20th Century rhythms. In fact, the opening title track contains plenty of off the beat rhythms that are a wonderful mixture of the ancient sound, with Barry's own style and the dramatic needs of the film. It shouldn't work, but yet it does, splendidly. This version contains several cues that weren't contained on the original album, notably the early Joust and Battle cue and the splendid Fanfare for Philip and The Great Hall Feast.

Perhaps of more interest to Barry fans is a suite from Mary, Queen of Scots. It's unfortunate that more from this score couldn't have been included as it's up there on the list of Barry scores that really ought to see the light of day on CD. The main theme is familiar from compilations, quite lovely in its simplicity. The highlights are perhaps the less familiar parts, the jaunty But Not Through My Realm being particularly wonderful; a bouncing woodwind figure over which is placed a longer line string melody.

The performance by the Prague Orchestra and Crouch End Festival Orchestra are typically excellent. They always are with their Barry performances, although I'd suggest that The Lion in Winter is more taxing than typical Barry. For The Lion in Winter, the better sonics are a definite bonus over the slightly harsh original album and of course the extra cues are of interest. This is likely the best we can hope for with regard to Mary, Queen of Scots, but it's a tempting sample from another great score. One great Barry score and a taste of another for the price of one make it well worth picking up, even if you already have the original Lion in Winter album.

Mary, Queen of Scots (1971)

The Lion in Winter (1968)

The Lion in Winter (1968)

Oscars: Best Original Score (Winner)

Trailer: